To some extent, the history of call centres is the history of customer service. Call centres shaped the service experience as we know it and allowed businesses to adapt to a global market.

The first recorded use of the term ‘call centre’ was just 35 years ago, in 1983. However, the history of call centres dates back further than that.

The first use of a call centre-like environment was in the mid-1900s, but we can go further still.

The call centre story starts (arguably) over 100 years ago, with technology invented in the late 19th century.

We’ve opened our textbooks and looked back at the history of call centres, from how they started out, to how they evolved over the years.

How did they come to shift towards the smart omnichannel contact centre of today?

The beginning

The key component of a call centre is the telephone. Without it, after all, call centres would have no raison d'être.

So, the history of call centres starts with the invention of the telephone in 1876.

The next component to a call centre was the ability to handle or direct multiple calls, a problem solved by the PABX (private automated branch exchange). This made for the beginnings of a switchboard, which followed shortly after the telephone in 1882.

An actor portraying Alexander Graham Bell speaking into an early model of the telephone

A switchboard operator circa the early 1900s

But invention doesn’t mean adoption. Before call centres could proliferate, the technology they relied on needed to be widely used. It’d take another 80 years or so before call centres as we know them started to appear.

So, fast forward to the 1960s, in the offices of major telephone companies. It was here that the first call centres were used to handle operator enquiries, and where the history of call centres starts its journey.

The growth

In the 70s and 80s, new technology meant that call centres were adopted into the mainstream by large businesses. They served primarily as a sales tool —the main role of call centre agents was calling consumers to sell a product or service.

The creation of a toll-free ‘800’ number for customers to use would change that. Call centres would now be taking and managing more inbound calls from customers responding to adverts and other marketing efforts.

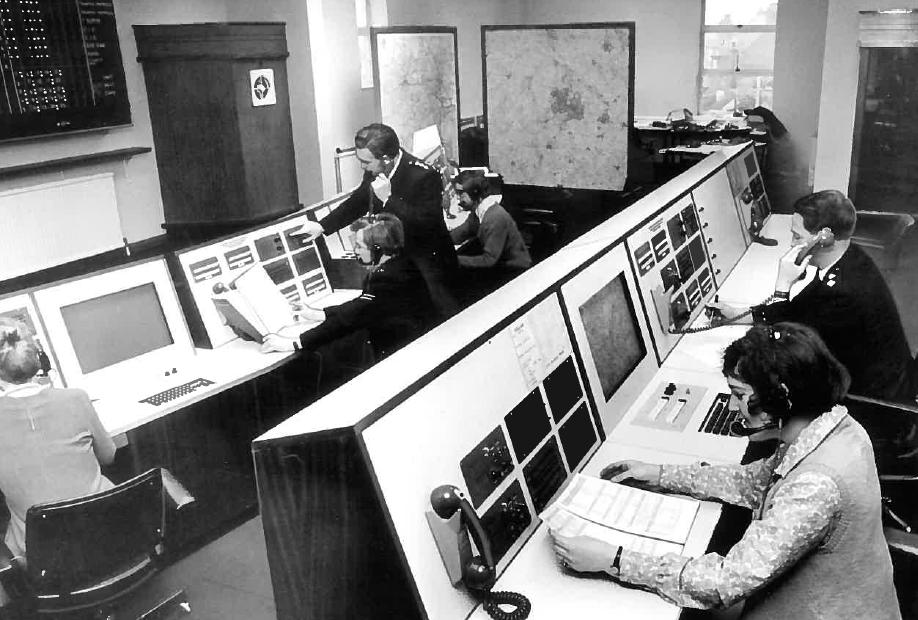

A 1970 police call centre

An operator in a 1980s call centre

A warning of things to come hit in the early 90s. Customer complaints led to the 1991 Telephone Consumer Protection Act, which restricted the activities of call centre agents.

Not only were restrictions placed on the times that call centre agents could reach out to customers, but automated diallers and messages were prevented as well.

But the history of call centres doesn’t end with this early restriction. The call centre continued its rise in spite of legislation.

The new law was an annoyance, but it also pushed agents to provide a more human experience with their outreach calls — a component of customer service that has become the norm today.

Internet impact

The internet also played an in integral role in the history of call centres. It was the internet that kickstarted the transition from ‘call centre’ to ‘contact centre’. This is down to the rapid rise of consumer internet access, and the ensuing popularity of email.

The 90s, in fact, saw email become one of the most popular forms of communication amongst consumers. Businesses needed to follow suit.

Email became a primary method of accessing support alongside the telephone, and found its place as a customer service channel within the slowly diversifying call centre.

But the 90s dot com boom was the real fuel feeding the fiery growth of call centres.

With an increasing number of companies operating online, there wasn’t always a physical store that customers could reach when they needed support. So, businesses turned to call centres to provide that missing element of customer service.

When the bubble burst in 2001, many call centres felt the sting. However, they continued to be a popular method of customer support for big companies, and those that survived the dot com crash.

Going offshore

At the turn of the millennium, the history of call centres saw an emigration to warmer sands.

With call centres still growing in popularity and use, cheaper labour costs prompted businesses to move their call centres away from the UK and into countries such as India, the Philippines and South Africa.

But this wouldn’t last long.

While call centres soaked up the sun offshore, customers started complaining about difficulty understanding agents over the phone due to language barriers. Businesses with offshore call centres also started to get negative attention from the media. The complaint was that they were taking away jobs from UK workers.

So, in the late 2000s, call centres started to return to the UK. (And they’re still moving back today.)

Companies used their UK location as a selling point, boasting of their UK based call centres, but damage had already been done.

The bad rap

Throughout the history of call centres so far, a negative reputation had been growing. They became hated by agents and customers alike, and moving offshore had aggravated problems further.

Having to contact a call centre was a chore. Many customers didn’t want to face painful automated phone trees anymore.

They didn’t want to abide waiting on hold, or handle hassled agents. They most certainly didn’t want to battle with language barriers.

With the growth of the internet and newer forms of communication competing with telephone support, telephone decline began to set in.

Receiving a call from a call centre was even worse. Cold calls were a nuisance, and receiving marketing calls became synonymous with intrusion and irritation. Even with the 1991 legislation in place restricting the hours they could happen, marketing calls continued to infuriate customers.

Agents, meanwhile, hated the management systems and conditions they had to work under. They went so far as to compare the call centre office with William Blake’s ‘dark satanic mills’.

The need to meet a quota left calling customers feeling uncared for, while stressed, tired and sometimes miserable agents struggled to offer attentive support.

The shift

Something had to change.

The term 'contact centre' started to gain recognition. The new name may have been adopted to help address the now pitiful reputation of call centres.

Contact centres are seemingly viewed as more professional, but this isn’t the only reason for the current shift towards the terminology change.

With the emergence of new communication technology, there came a push to giving an omnichannel experience. This meant creating a melting pot of contact options, rather than separate channels for customers to use. Call centres weren’t just handling telephone calls anymore, and the name no longer fit.

Now, customer service agents had a plethora of different ways they would contact customers. Emails, SMS, snail mail, live chat software, social media and chatbots became part of the fray.

Call centres became a central hub of contact, rather than calls alone, and the name change reflected this.

Looking to the future

Call centres took a while to get off the ground. But once they did, they became a core part of customer service. The history of call centres is studded with both technological and operational progress, defining the customer experience as it is today.

Now, we’re closing the book on the history of call centres. Instead, we face a future of omnichannel, AI-powered contact centres.

If history is anything to go by, it’ll be a future of instant, real-time support with a twist of the human touch.

Useful links

- - The evolution of customer service technology

- - The history of live chat software

- - Telephone decline: the battle between calls and chat

- - A brief history of the age of the customer

- - The alterned nature of telephone customer service

- - The death of standalone contact channels